Using outcome measures and feedback tools as vehicles for trust

We know that good therapeutic relationships are considered a central component of effective support (e.g., 1–3). Young people have described recovery from mental health difficulties as being reliant upon supportive relationships, which in turn are built on working towards agreed areas of focus (4,5). The importance of meaningfully using outcome measures with young people is something we have talked about for many years. This means actively discussing the ratings on the scale with the young person, and where possible using these discussions to inform the intervention with them. Afterall, we know that involving young people in decisions about their care has been demonstrated as empowering and conducive to better quality of life outcomes and satisfaction (6,7).

The presentation of the young person has also been mentioned as a challenge to the implementation of outcome measurement. For example, practitioners have discussed the difficulties of engaging young people who are in high levels of distress, or who have experienced trauma in any discussions about outcome and feedback tools. In our own research on goal setting, young experts by experience also said that if they were in high levels of distress, they might not know or be able to articulate, what their goals for therapy might be. They also said that if they had experienced trauma and were referred for long term therapy, it might be hard to order their thoughts, or to be able to think about what their end point goals [or outcomes] might be (10).

Nevertheless, we found that in a general sense, goal setting can provide a shared language, a shared understanding and a common ground, to help to build trust within therapeutic relationships, to enable work to move forward (10). Building on this, and from a clinical perspective, Duncan Law recently published an opinion paper (11) in which he explores the current reticence of practitioners to incorporate a focus on goals in support to young people who have experienced trauma. Law delves into how people who have experienced trauma perceive the world, and learn from others in it. Law discusses ‘mentalization’, which is one person taking interest in another’s mind, and in their intentional mental states, which builds understanding and trust between people (12).

What does this mean for practice?

Law highlights that practitioners often have reservations when faced with setting goals with young people in high levels of distress and/or who have experienced trauma, because they are often perceived as not knowing what they want out of the therapeutic process. This aligns with what young people told us when we spoke to them about goal setting (10). Importantly, Law encourages practitioners to think about the difference between a young person who doesn’t know what they want, and a young person who doesn’t dare share what they want, due to a distrust in people, arising from their experiences of trauma. That is, where the young person doesn’t trust the practitioner enough to risk sharing their vulnerabilities yet.

This idea of ‘yet’ is a really important one. There is sometimes a need to rush to get baseline information on outcome measures, but this needs to be balanced with the meaningful use of measures. Such that it might take a few conversations to be able to determine what someone’s goals might be. Law also discusses that the use of the GBO (and this is also true of outcome measures more generally) can become a tick-boxing exercise, where the data are collected and sent off with no further thought. This undermines the fundamental – and meaningful – use of outcome measures. In Law’s words: “to engage with a person to understand their story, their background, and their future-oriented intentions and wishes in order to create this atmosphere where the client experiences the therapist’s intention to care.” (5, p.4).

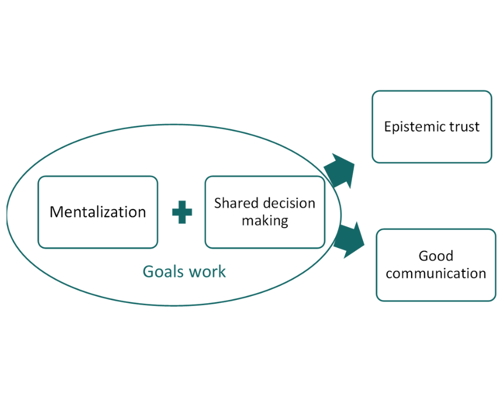

In summary, Law argues that goals are an important part of the multifaceted process of shifting mental health difficulties, grounded in showing an interest in the young person’s life and their challenges. This is achieved through mentalization (12) and shared decision making (13), of which goal setting is a central component. I recently presented Law’s paper, amongst others, at our CORC Members’ Forum. I conceptualised the main takeaways in this diagram:

While Law centres on goal focused work, and the meaningful use of tools (e.g., the GBO) to support this, the learning here could also be applied to other outcome measures too. If perceived and used as conversational tools that help the practitioner learn more about the young person’s difficulties, then perhaps this too might lead to a sense of taking an interest in the young person, which builds trust. This of course means that they need to be thoughtfully selected for each individual young person and discussed in meaningful ways.

The real message here is the acknowledgment that it is complex to have conversations about outcomes and outcome measurement with young people who have experienced trauma, but trying to engage with young people about what they want is a necessary part of the therapeutic process. The highlighted positive links between collaboratively working on goals and building trusting relationships make efforts to engage in meaningful conversations about outcomes, including goals, is even more crucial for work with young people who have experienced trauma.

Dr Jenna Jacob, December 2022

References

- Castonguay LG. Predicting the effect of cognitive therapy for depression: A study of unique and common factors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;497–504.

- Messer SB. Let’s face facts: Common factors are more potent than specific therapy ingredients. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2AD;21–5.

- Kazdin, A. E., Whitley, M., & Marciano PL. Child–therapist and parent–therapist alliance and therapeutic change in the treatment of children referred for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):436–445.

- Leavey JE. Youth experiences of living with mental health problems: Emergence, loss, adaptation and recovery (ELAR). Can J Community Ment Heal. 2009;24(2):109–26.

- Simonds LM, Pons RA, Stone NJ, Warren F, John M. Adolescents with anxiety and depression: Is social recovery relevant? Clin Psychol Psychother. 2014;21(4):289–98.

- Asarnow JR, Jaycox LH, Tang L, Duan N, LaBorde AP, Zeledon LR, et al. Long-term benefits of short-term quality improvement interventions for depressed youths in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1002–10.

- Richardson, G., & Partridge I. Child and adolescent mental health services liaison with Tier 1 services: a consultation exercise with school nurses. Psychiatr Bull. 2000;24(12):462–3.

- Fleming I, Jones M, Bradley J, Wolpert M. Learning from a Learning Collaboration: The CORC Approach to Combining Research, Evaluation and Practice in Child Mental Health. Adm Policy Ment Heal Ment Heal Serv Res [Internet]. 2016;43(3):297–301. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-014-0592-y

- Gelkopf M, Mazor Y, Roe D. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measurement (PROM) and provider assessment in mental health: Goals, implementation, setting, measurement characteristics and barriers. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2021;33(1).

- Jacob J, Stankovic M, Spuerck I, Shokraneh F. Goal setting with young people for anxiety and depression: What works for whom in therapeutic relationships? A literature review and insight analysis. BMC Psychol [Internet]. 2022;10(1):1–15. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-022-00879-5

- Law D. Working with Goals and Trauma in Youth Mental Health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17).

- Fonagy, P.; Allison E. The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy. 2014;51(3):372–80.

- Coulter, A., Edwards, A., Elwyn, G., & Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the UK. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes. 2011;105(4):300–4.